Much has changed since I last sat down to write about Mei Hachimoku’s recently concluded series The Mimosa Confessions. Mark Hamill, or at least someone using his account, read my post about Stephen King and liked it enough to click the big heart button. I fear I will turn to dust if that somehow made it to Stephen himself. If you see a trailer for Rob Zombie’s Maximum Overdrive, remember me as a hero. For now, it’s time to come home: back to gay anime.

-Spoiler Warning-

There is no shortage of gender-diverse characters in anime and manga, but The Mimosa Confessions stands in rare company as a series centering an explicitly transgender character in a grounded setting. The events of the novels follow the perspective of protagonist and semi-professional rake-stepper, Sakuma Kamiki after his now estranged childhood friend, Ushio, begins her gender transition. Further, Ushio confides her long-held romantic feelings for Sakuma, leaving the two to navigate both who they are and who they are going to be for each other while coming of age in a semi-rural community.

Even though Ushio’s transition is the catalyzing event in the series, she is a black box — her thoughts, feelings and motivations are her secrets not to tell. Hachimoku stays committed to telling the story through the first-person perspective of people around Ushio, and his restraint as an author further elevates the series. Horror fans will tell you two things: first, that no live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality and second, that the monster you imply will always be scarier than the monster you show.

Engaging with a narrative like this becomes a self-reflective exercise. Speaking for myself, you may be shocked to know that I am not a teenager growing up in rural Japan in the late aughts. I am a queer woman on the wrong side of 35 that grew up in the American midwest. I look forward to finding out how it may differ from the reading of someone who doesn’t have a fight or flight reaction to the question “Where is your boy tonight?” (Some of you just thought “I hope he is a gentleman.” This is how I use my psych Ph.D lately)

You can read my detailed writings on the first three volumes of the series here and here. Going into the fourth volume, Ushio has found herself more popular than ever. The love triangle between herself, Sakuma and their classmate Natsuki has collapsed, leaving Sakuma and Ushio to become more than friends. The third volume even closes with Ushio pinning Sakuma to his own bed in a scene that had me wondering if I was about to learn if Mei Hachimoku knows what frotting is.

%20Vol.%203%20-%20Google%20Play%20Books.png)

The fourth volume opens with a middle schooler paraphrasing Voltaire, as is tradition. To Ushio’s younger sister, Masao, their birth mother was a stable and seemingly invincible figure in her life so much so that she likens her mother to God. Then, she watched her god fall ill, decline and die, leaving behind a hole in her understanding of the world and her own place in it. Since god no longer existed, it became necessary to invent one out of her admiration for her older sibling.

Years later, she would come home to find Ushio wearing a girl’s school uniform, upending both her idea of who her sibling is and who she is in relation to her. Mustering the indignant scorn only a ninth grader can, Masao berates her sibling until Ushio flees the house, leaving her to wonder if this really should have been a surprise. Through Masao’s perspective, the story traces the thread of her relationship with Ushio in reverse chronological order.

In one vignette, Masao finds a cosmetics bag while returning something to Ushio’s room. Whomst amongst us has not had the hidden cosmetics bag of shame tucked away somewhere in a bedroom at some point? When confronted with pretty obvious evidence that her sibling might have an interest in presenting more femininely, Masao pulls a gold medal in mental gymnastics instead, reasoning that it must belong to her brother’s secret girlfriend who somehow snuck in for whatever a ninth grader thinks an illicit rendezvous looks like. It’s not enough that her sibling is successful, attractive and popular, Ushio also needs to be “normal” i.e. cishet, traditionally masculine but actively performing heterosexuality.

I was particularly struck by one of the earliest vignettes where Masao confides to Ushio how she wishes she had also inherited their mother’s blonde hair instead of being stuck with the player 2 color palette. Ushio sullenly responds that they actually admire their sisters' more conventional color and wish they could just be “normal.” I grew up with a large extended family where every woman was born blonde and I was the only blonde boy (heh).

At school, I was bullied for my hair being “girly.” At home, I was told how much my hair made me look like a girl in the family. On one hand, part of me was happy to hear it. Another felt like my hair had been wasted on me. A third secret part, felt like my body was betraying something to the world that I was too ashamed of to speak aloud — that I wanted to be should have been born a girl. This whole scene is barely more than a few pages but is a stellar example of Hachimoku’s efficient prose inviting the reader to make their own interpretations and rewarding them for it. Another reader might pass over this vignette but it hit me like a Hind-D helicopter.

Ushio, unfortunately, isn’t the only person Masao is lashing out at. Their stepmother, Yuki, hasn’t given Masao a reason to dislike her — that’s actually the whole problem. Yuki is kind, feminine, affable and competent in so many ways that their mother wasn’t. Yuki is the kind of person who cooks from scratch. Masao’s birth mother was the kind to use a mix, throw away the box only to fish it out of the trash to read the directions. Still, Masao remembers her mother from the perspective of a child. Yuki’s presence in the house gradually whittles away at her idealized memory with nothing else to replace it.

Masao lost her mother at an age where she hadn’t yet learned that your parents aren’t perfect. She avoided processing her grief by shifting her admiration to an increasingly unrealistic image of her sibling Still, holding onto those ideas gave her a feeling of stability in an uncertain world. Letting go of the person she thought Ushio was and accepting Yuki also means processing the death of her mother and she isn’t ready to do that. Her life-preservers having been taken away, Masao isn’t just treading water — she’s thrashing.

Masao could have been written as being flatly transphobic but her character has a level of nuance where you can trace the thread of how she got to be who she is. Trace it far enough and you’ll find it terminates in a tightly wound knot. There is a path forward for her, but whether she will take the time and effort to unravel that knot is up to her. In the final act, Masao finds it in herself to start calling Yuki her mother but calling Ushio her sister is still a bridge too far. Ushio seemingly acquiesces but later admits that she’s willing to sit with her discomfort for another year if it means Masao will stop acting out. After that, she’ll move away for college and cut off her younger sister if she can’t get with the program. Masao’s absence from the fifth volume epilogues seems to imply that may be the case.

As a reader, I was expecting the novel to end with Masao calling Ushio her sister for the first time. Instead, I was caught off-guard by a bittersweet resolution that struck a little too close to home. About ten years ago, I called my sister to come out to her as transgender. She did not take it well eeking out “you’ll always be my older brother” through tears before hanging up the phone on me. Which was, of course, missing the whole point of the call in the first place. She hasn’t spoken to me or acknowledged we’re even related since. Needless to say, this scene pulled something out from a dusty corner of my mind that I try to ignore. It’s a bitter pill of an open ending but sometimes that’s just life.

Separate from the family drama, the volume is also peppered with overtures between Sakuma and Ushio and whether Sakuma can or will return Ushio feelings. Their exchanges are endearingly awkward as only high schoolers’ can be, all culminating in Sakuma finally returning Ushio’s feelings. Neither are sure things could work between them but are willing to take the risk.

If this was the coda for the entire series, I’d have been content. If I were to be indulgent, I’d ask for a cherry-shaped epilogue on top following up with Sakuma and Ushio months or years later. It wouldn’t be a cleanly happy ending but Hachimoku’s other novels have also had complicated endings where not everything works out as planned — except for that one where winning the lottery really does solve almost all your problems.

Unfortunately, this isn’t the coda for the series.

Being totally honest, this last volume has been challenging to write about. Criticism walks a fine line between being unfair and repeating “I wanted it to be different” ad nauseum. As a reader and writer, I find both of these tedious at best. What makes this conclusion so frustrating is how the seeds of a much stronger resolution are planted there. Like Homer building the grill, the pieces are there but they don’t quite come together. There’s also a few baffling extras tossed in there and you’re not sure where they came from. The result is a novel that is not only less the sum of its parts but maybe the weakest novel I’ve read from Hachimoku.

How did that watch get around that board?

How did that watch get around that board?

The fifth novel opens with Sakuma and Ushio having quickly run aground. Sakuma has been taken by his old flame, stepping on rakes, as his unrealistic ideas about relationships keep getting in the way. Ushio isn’t happy with the situation either, although Sakuma is too in his head to notice. Adding pressure to the situation, word that they’re dating also gets out just before heading out on an overnight school trip where they’ll be around each other constantly. They break up and get back together after Sakuma realizes how badly he’s been fumbling in time to perform the customary teen feelings™ grand romantic gesture. A final epilogue closes the series with the two of them still happily together years later.

The big picture moves of the plot aren’t the problem. If anything they’re endearingly quaint. The problem is how the specifics of those moves are disconnected from the rest of the series. With nearly every loose end wrapped at the end of the previous installment, I was hoping this would be a victory lap building on what came before. Instead, the narrative seems more interested in untying those ends just to retie them again. By the time the narrative was relitigating the love triangle; I felt like Mei Hachimoku had just broken my ankles on the court.

Ushio’s main growth edge has been her reclaiming a sense of self-worth and yet here she is acquiescing to a relationship with a guy who doesn’t seem that interested. Sakuma, who ended the prior volume seeking out a relationship with Ushio, doesn’t seem to be actually trying either. Perhaps worst of all, early in the novel Sakuma goes through a flashback of pre-transition Ushio just as she is about to kiss him and pulls away in what feels unnecessary at best and gay panic at worst.

I genuinely don’t know how to interpret this move — the novel doesn’t seem to either. The most charitable reading is that Sakuma is already anxious because being in a relationship doesn’t feel the way he thinks it should. Ushio goes to kiss him, the anxiety devils hit him with the worst intrusive thought possible. But at the end of the day, the scene reintroduces the idea that Sakuma doesn’t think about Ushio as a woman, which was seemingly resolved in the very first volume.

Once the “Sakuma doesn’t see Ushio as a woman” seed has sprouted, it grows like kudzu over everything that follows and makes it hard to feel good about later developments. I’ve already seen one read on the seemingly happy ending that reframes it as a tragedy where Ushio settles for a relationship with someone who doesn’t fully acknowledge her as a woman. It’s a very very sad conclusion that seems so detached from the prior direction of the series, but also one that I can fully understand how someone could come to.

Not to play editor but to play editor, let me pitch something. The story opens and things are going ok. Sakuma says the right things but Ushio is frustrated that she has to ask for physical affection (i.e. touching her canonically chiseled abs). Stress builds and she starts to doubt whether Sakuma is actually attracted to her or even if he sees her as a woman. To borrow a phrase — She wants him to want her. She needs him to need her. This sets up the later events of the story while building on the existing character work.

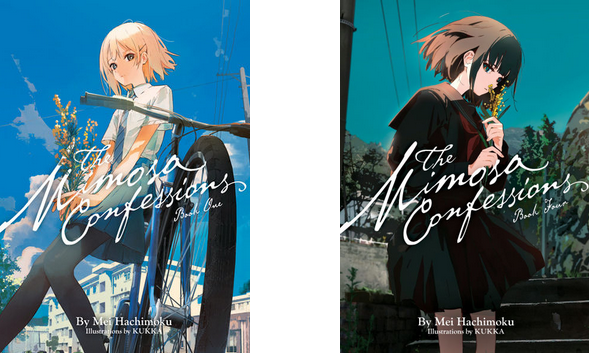

One of those later events is, in my opinion, the strongest moment in the entire series. Sakuma confides with Natsuki about his struggles in dating. Having been a prior part of the love triangle plot, Natsuki lets Sakuma know that he’s actually very easy to read (It’s a novel from his perspective after all) and isn’t totally aware of himself including how he looks at Ushio. This volume was already frontloaded with Kukka’s stellar insert art but this line completely recontextualizes the way the art has worked in this series.

How spicy could this soup really be? - A fool, 20XX

In early volumes, Ushio is ethereal, facing away and disconnected from the rest of the composition. In this last volume, she’s solid, central in the composition and lit with vibrant value contrast — this is Ushio seen through the eyes of someone who loves her. This one move reframes the art as an integral part of the narrative both within this volume and across the series while elevating both halves into a greater whole. The realization that he is deeply in love with Ushio, even if their needs in a relationship and ideas about love might not perfectly align also gives Sakuma the motivation to move into the final arc of the story. Just imagine that I’m doing the pinched fingers gesture while typing because it’s just *chef’s kiss*

Sakuma’s journey to realizing that he is in love, unfortunately, also has some of the lowest points in the series. Much of this part of the narrative plays out via exchanges with Sera, a former antagonist turned antagonist (?). Sera is polyamorous and has drastically different ideas about love compared to Sakuma. The main throughline in their exchanges is how Sera, through the honorable dude art of ribbing, tries to get Sakuma to realize that different people have different needs in a relationship and how badly he’s self-sabotaging this relationship. When the topic of sex comes up, Sakuma admits that he hasn’t even thought about how he and Ushio would have sex. I was expecting this to be a springboard for Sakuma to realize that he may be asexual.

Nah, it’s an evil bisexual polycule. Sera has been trying to convince Sakuma into giving up on Ushio because he’s the one that Sera is really interested in. Surely this is explored and developed, right? Nah, it’s dropped almost immediately and never mentioned again. Sakuma does say that Sera looks disappointed by the rejection but that he isn’t sure if he’s doing a bit or not. Dear reader, had I not been four volumes invested in seeing how this story ends I would have dropped the novel faster than it dropped the evil bisexual polycule. It is utterly baffling.

There might have been something really special if the narrative had gone the asexual route instead of the evil bisexual polycule. So let’s imagine if Sera instead said “Dude, have you considered you just might not be that into sex, like, generally?” Framing the narrative around Sakuma’s attraction to Ushio and not his relationship with intimacy generally retreads a settled issue in the narrative instead of a more interesting move by turning the narrator’s focus inward. Sakuma has spent the series thinking of himself as “normal” but this would give him something personal to process which connects to the series' bigger themes of how there really is no such thing as being “normal.” There are shades of this already in the narrative but it’s quickly handwaved in the epilogue in a single line that amounts to “and I’m normal now.”

It’s made all the more frustrating having binge read the Otherside Picnic novels while organizing my thoughts. That series has similar elements but dedicates an entire volume of space to one half of the lead couple processing her potential asexuality and the two of them working through what that means for their relationship. It’s a strong recommend.

Many people are saying this

In visual novels, it’s a common move to seed teasers of other story routes into each playthrough. It makes the world feel bigger and encourages the player to imagine where those paths might lead to. Part of what makes the ending of this series so frustrating is how easy it is to imagine those paths not taken. The prior entries have taught and rewarded the reader for making inferential moves in ambiguous narrative space. Here, you're locked into a route where Sakuma keeps picking the “bad end” dialogue options with no way off the ride.

There isn’t a better illustration of this playing out than in an early scene where Ushio is clocked by a group of students from “the big city” who start laughing at her. This could have been a moment where Sakuma defends his girlfriend and realizes that just because Ushio “passes” and is very conventionally attractive doesn’t mean that her life won’t be hard. Some effects of masculinizing puberty can’t be undone (at least until scientists develop the Bioshock 2 voice surgery for vocal feminization). The world is not a fair place and committing to being her partner also means committing to support her through that. Sounds good right? He just stands there and watches it happen while overthinking whether he should say something.

Endings are already hard to write and I don’t admire the task of trying to write an ending where openess has been a selling point in the narrative. Most of the plots in the series had already been resolved going into the final volume leaving an ending that feels like too little butter scraped over too much bread. The parts that feel tacked on come off as overwritten, leaving the parts of the story that do work feeling comparatively underwritten. I would have been happier had an aggressive edit dramatically shortened the main narrative leaving space for more interludes playing with perspective, space and time: Maybe Ushio’s acceptance at school inspires another student to come out and she finds herself navigating a mentorship role or maybe years down the line Masao and Ushio reconnect after a long period of no contact, etc., etc.

Unfortunately, it seems to be a genre convention for fiction centering trans characters to have conflicting endings. It really does just keep happening. Despite that, I don’t regret my time with this series. I'm still very warm on it actually. I’d even still recommend it albeit with slightly more hesitation than before. That I’ve written as much as I have here goes to show how much of a reaction it got out of me. It really does feel like riding a rollercoaster complete with high highs, low lows and an unfortunate drop toward the end. So I’ll end it here. The car is coming to the station. The ride is finally over.

Until scientists deduce why so many characters with complicated gender feelings are blondes with bobs, be nice to yourself.