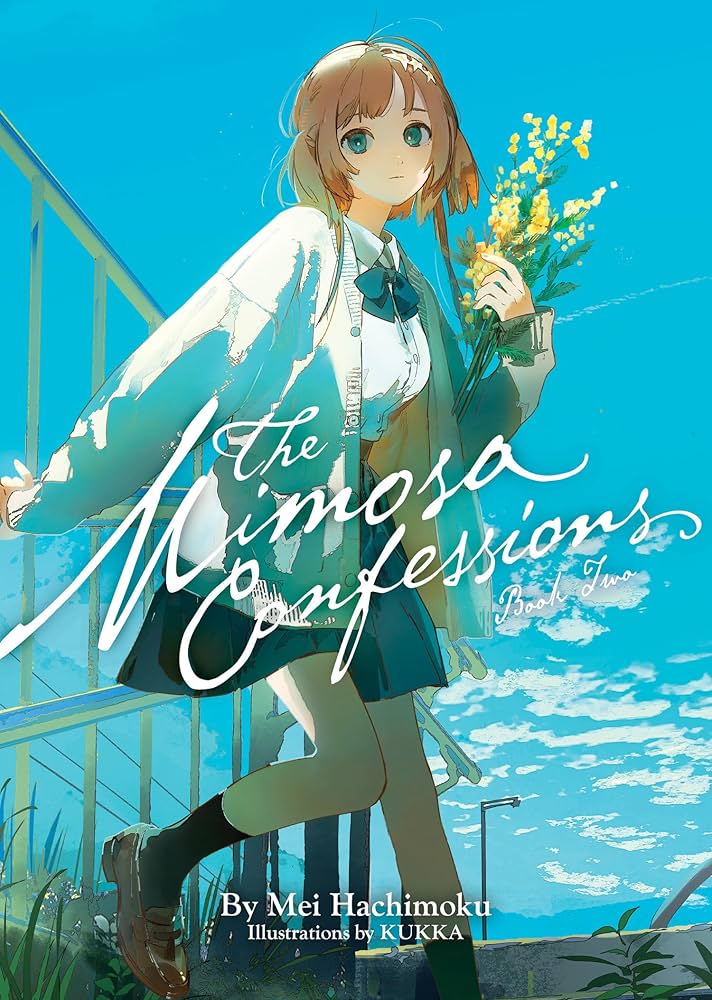

The Mimosa Confessions Volumes I and II

Last week, I read the second volume of The Mimosa Confessions and it’s been kicking around in my head. Rather than editing together a long tweet thread about it, I decided to start posting these kinds of things with the recently unearthed technology known as a blog. Scholars say blogs were like tweets but longer but really who can say.

I learned about this series via a comment on my most recent youtube video (like, comment, subscribe, etc). I read the promo blurb for the series and instantly regretted not delaying the video a few weeks for the English release of the first volume – I almost certainly would have included it. One of the points I made in that video is the asymmetry in the number of stories that deal with trans identities via allegory, whether it be magic, science or the increasingly common “rapid onset sex change disorder”, and the stories that deal with explicitly transgender characters in a real-world setting.

Source: Watashitachi wa Moto Joshi desu

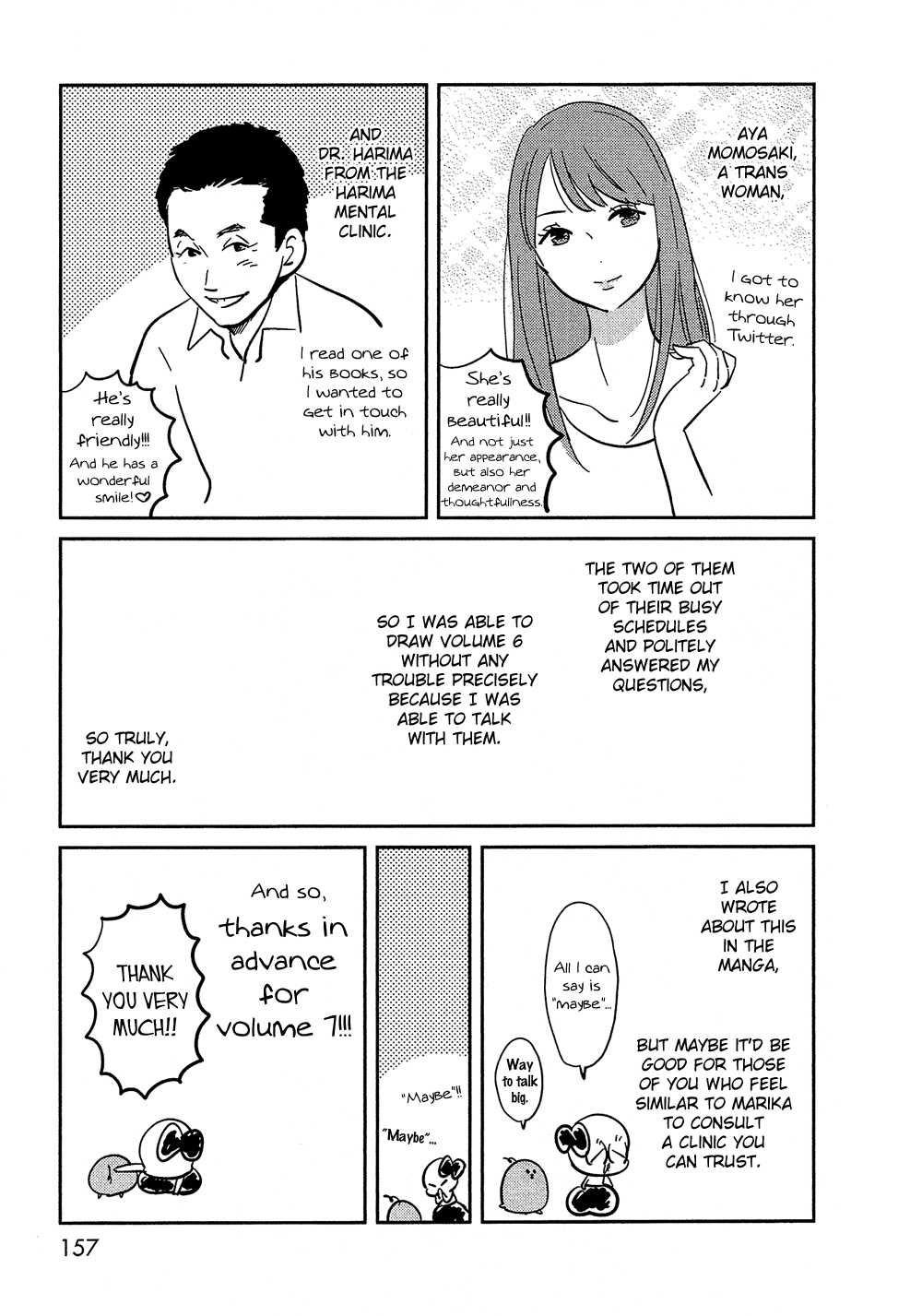

Of those few, I compare and contrast the depictions of trans characters in Takako Shimura’s Wandering Son and Fumiko Fumi’s Bokura no Hentai (Our Metamorphosis or Our Perversion). In reading Bokura no Hentai, I was struck by the amount of research that went into writing the story’s trans character, Marika. Wanting to depict the experience of a trans kid as accurately as possible, Fumiko Fumi went the extra mile of talking with a doctor as well as a trans woman to get their perspectives on what the process might be like for an adolescent seeking gender affirming care.

Similarly, The Mimosa Confessions aims to reflect what the experience of a trans teenager might be as they navigate the early phases of transition. Series author Mei Hachimoku also went through an extensive research process in developing the novel’s trans character, and it shows. I came across a reviewer saying the novel had given them “secondhand gender dysphoria.” Having only read the first two of five total installments in the series; I’d believe it. I’d even admit that I may have caught some of it myself.

Similarly, The Mimosa Confessions aims to reflect what the experience of a trans teenager might be as they navigate the early phases of transition. Series author Mei Hachimoku also went through an extensive research process in developing the novel’s trans character, and it shows. I came across a reviewer saying the novel had given them “secondhand gender dysphoria.” Having only read the first two of five total installments in the series; I’d believe it. I’d even admit that I may have caught some of it myself.

So what is this story actually about?

-MINOR SPOILERS-

The main character, Sakuma Kamiki, is a dude™. He’s not particularly smart or athletic, he has a crush on a girl in class, Natsuki Hoshihara, and his childhood friend, Ushio Tsukinoki, has become the prince of the school as the two drifted apart over time. So yeah, he’s a light novel protagonist. One night while walking home, he comes across Ushio wearing a girl’s school uniform and crying uncontrollably on a park bench. Not long after, an announcement is made that Ushio is attending school as a girl, which sets in motion the events of the series.

As much as The Mimosa Confessions shares a skeleton with other YA love triangle stories, the inclusion of Ushio and the rippling impact of her transition casts familiar tropes in a new light. Sakuma likes Natsuki. Natsuki liked Ushio prior to her transition but isn’t sure what to call her feelings now. Ushio herself confides that she has had romantic feelings for Sakuma for some time. As of the ending of the second volume, it seems pretty clear how this is going to resolve. I’d even put money down on it. However, the romance is secondary to the evolving dynamics, stumbles, and successes that come into play as Natsuki and Sakuma have to confront their own evolving feelings around sex and gender while supporting Ushio in her transition; trying to understand someone who has set herself on a very different life course than themselves.

Another strength of the series is the use of a first person perspective. Other similar stories that I’ve read recently have typically employed a third person perspective where the reader has access to the inner worlds of each of the major characters. Why characters do what they do and feel what they feel is made clear to the reader. Not the case here. We only get to see the events of the story unfold from the perspective of Sakuma: perhaps the most cishet boy there has ever been.

As much as the events of the story center around Ushio like the planets revolving around the sun, we readers never get to know why she does what she does. We know she has a difficult home life with a step-mother she isn’t close with and a sister that is vocally opposed to her transition, but it’s never something we get to see. We just get Sakuma’s conjecture that Ushio’s complicated homelife might be the reason she’s spending so much time at Sakuma’s house over summer vacation. Through the events of the series, Ushio is a black box.

It’s not as relevant to the story, but it also means we don’t actually know what her transition actually consists of or how she relates to her body. Other characters mention her voice is husky, even after she starts speaking in a more front resonate voice, so presumably she’s gone through – or is still going through – some degree of a masculinizing puberty. But unlike in other similar stories, anything beyond that is not privileged to the reader.

It was after a particularly dramatic turn in the later half of the second volume that I set the book down and thought to myself, “Damn, Ushio might actually kinda suck.” It was seconds later that I was crushed by the weight of self-awareness and realized that I was projecting my own prospective rationale onto the character. It was, in fact, me who might actually kinda suck. I hadn’t even thought too hard about doing it, it just happened. It speaks to the quality of the character writing that I found myself motivated to fill in the blanks in an effort to better understand the character.

I expect that different people might have very different readings of Ushio. For example, I’m roughly twice the age of the characters in the story. I’m also probably twice the age of the youtubers mispronouncing “mimosa” that I stumbled on while searching around for other people’s opinions. (I don’t know what’s scarier: that they're too young to order alcohol, or that they are and no one thought to correct them, like how my friends let me mispronounce Stella Artois for years). While I’ve been a high schooler in the suburbs of Chicago, I’ve never been a high schooler in rural Japan. Shocking, I know.

So my life experience doesn’t map cleanly onto the events in the story, but there are plenty of moments that resonated with me. When Ushio tells Natuski not to worry about her getting in the way between her and Sakuma because “Saukma doesn’t like guys”, or that Sakuma only like “real girls,” it stings because I know I have also seen being trans as something that makes me less than cis women around me. When she excuses herself after being gushingly complimented by classmates so she can go cry alone, I assume it’s because she also can’t trust that anyone could sincerely think those things about her. When she makes moves toward dating someone that doesn’t seem to respect her, well, that’s a long story best left unwritten.

On the other hand, having the story told through the perspective of a cishet boy is also surprisingly compelling to me. As much as I’ve found myself in situations that resonate with some of the events in the story, I have only seen them from my own perspective, hence Sakuma’s perspective is about as alien to me as Ushio’s seems to be to him. At times, it can even be kind of funny.

One scene in the second novel reminded me of a moment from several years ago. I was at a fighting game tournament and meeting friends from around the country for the first time since coming out. I’m hugging some friends to say goodbye after hanging out, and one guy, someone I thought of as a friend and had known for years, but never been around presenting femme, goes to give me something between a handshake and a hug. I laugh and ask him what he’s going for, and I have never seen someone turn redder either before or since. He quickly said something about needing to go to his car and bolted out of the lobby.

It’s like watching as a switch flips in someone’s head where they suddenly realize they’ve been talking to a woman – heaven forbid, maybe even an attractive woman – and something shorts out in their brain. Reading something similar but told from the other side was kind of fun, both in feeling bad for Shakuma, chuckling at his newly developed inability to look Ushio in the eye and knowing that Ushio can probably tell what is going on in his head.

It’s a fun example of the real heart of the story. Romance aside, it’s a sincerely told story about two childhood friends trying and sometimes failing to close a widening distance between them. Any prospective romance between them is just icing.

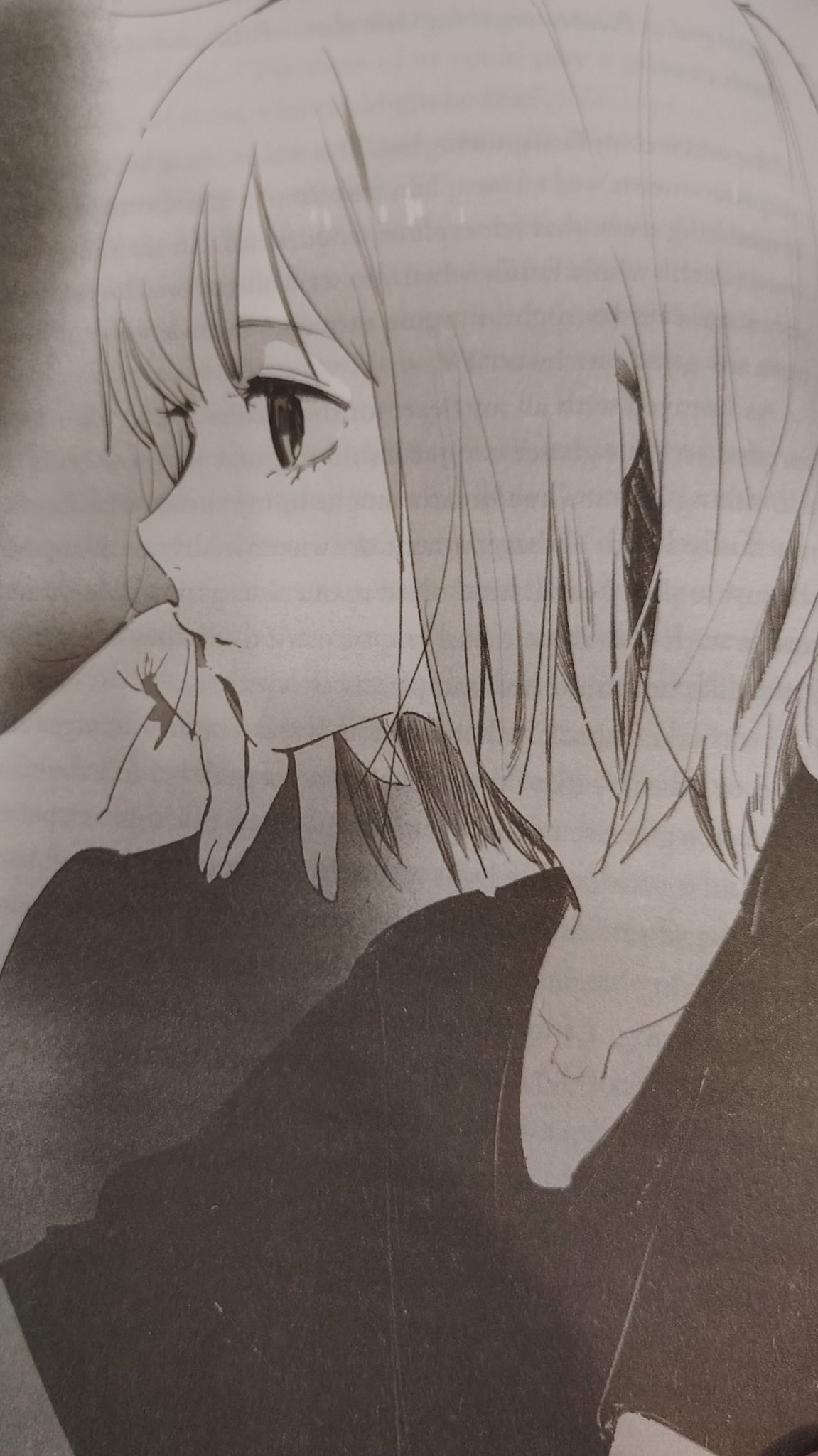

That theme is echoed in Kukka’s stellar artwork. The covers are striking, with dynamic perspective that makes the characters appear gigantic, minimal use of lines, gorgeous use of value contrasts, and reflected light from the highly saturated backgrounds bringing in a wealth of color variation. But it’s the greyscale insert art that stuck with me after putting down each volume.

If you can’t tell, I’ve spent the last few months trying to lock-in and really learn how to draw. In that process, I’ve thought a lot about composition and particularly the shorthand rules for composition in character illustration. Those rules are mostly followed in Kukke’s insert art. Characters are facing the viewer, fill most of the panel and centered in the overall composition of the image. Those rules are, however, noticeably broken for art focusing on Ushio. She’s often off-center, at-distance, and looking away from the viewer or blending into the background. To the extent that the inserts are intended to be snapshots of Sakuma’s perspective, it highlights the disconnect between them.

The insert art of a scene where Sakuma looks over at Ushio while they’re watching a movie especially comes to mind. She’s centered and filling the page, since the two of them are close in physical space, but she’s shown in profile, paying no attention to him, as if they’re on entirely different planets. He might as well not even be in the room. Art is cool and dumb like that, where breaking the rules of composition with intention can itself create an effective composition.

This has already ended up being longer than I had intended so I’m going to end it here. It’ll be a few months until Seven Seas releases the next volume so maybe I’ll flex my little baby N3 muscles and import the Japanese volumes to read ahead in the series. For now, I’d give the series a strong recommendation: three genders out of two. I can foresee that there will be another post about it in the future. Until then, be nice to yourself.