When we were a proper country, anime was confined to the Toonami programming block on Cartoon Network. As a good American, I’d dutifully sit to watch the “action cartoons” once I got home from school. Then, 9/11 happened. It’s not relevant at all to the topic at hand, but just putting things in context.

As I got older, wiser and I learned about the internet outside of America Online, anime broke containment. Of all the series I learned were split into three-part videos on youtube, one loomed heavily on my young mind; Rumiko Takahashi’s Ranma ½.

Having known I was trans for as long as I knew gender existed and already a seasoned veteran of the repression wars, I was drawn to a series about a boy able to turn into a girl and back again. I also knew not to touch hot stoves. So I filed it away and melodramatically vowed, in the way only a depressed teenager can, to never read or watch it.

Surprisingly, that has actually panned out. Yes, all of my exposure to Ranma ½ has been entirely secondhand as of writing this – and there has been a lot of it. Ranma is a cornerstone within the world of anime and manga with breakout success in international markets, making it impactful in the western media as well. That influence is felt especially strongly among queer creators. Sara Soler’s autobiographical comic about her wife’s transition, Us, specifically shouts out watching Ranma as a lightbulb moment for her wife in realizing her transness.

Maybe it’s not surprising that a series about gender transformation is appealing to queer audiences. In other news, water is wet. However, what is surprising is how different those readings of the work can be from academic media critics who engage with the text. Like Susan J. Napier, in her essay “Akira and Ranma 1/2: The Monstrous Adolescent”, which makes a compelling argument that Ranma ½ is a conservative work and not just by modern standards. Heck, “Stop!! Hibari-kun!” was published years prior in the same magazine.

In this view, the series uses transformation to reinforce, rather than challenge, an essentialist understanding of gender. Even in moments where Ranma’s transformations are transgressive, the format of the series means that events are always headed toward a conservative resolution. The series situating itself in the “real world” also means a return to a cishet normative status quo before the end of the episode.

This reading could not be more different from Angela Davis’ article “One Classic Anime Was So Forward Thinking, It Inspired My Personal Queer Discovery” which praises Ranma as a genuinely progressive work ahead of its time specifically pointing to an episode in the series third season “Am I Pretty? Ranma’s Declaration of Womanhood.” In the episode, Ranma hits his head, develops amnesia and comes to believe he is a girl who becomes a boy and not a boy who becomes a girl. Until a second head injury returns things to normal, Ranma adopts a stereotypically, nearly satirically, feminine persona. Davis sees this episode as the show demonstrating Ranma coming to enjoy femininity and points to it as her own personal “egg-cracking” moment.

Napier also comments on this exact episode but highlights how the episode casts these events as humor rather than drama. New Ranma’s feminine manner of speaking is derided as talking like an “okama”; a homophobic slur for feminine gay men. Other characters that had previously rejected Ranma’s feminine form accept this new version of the character, but only when Ranma conforms to a traditionally feminine gender role. This new Ranma can be accepted as a woman only insofar as she doesn’t challenge anyone’s idea of what a woman is.

Is Davis wrong for making a personal connection to the series that ended up improving her life? Hell no. There’s beauty in our ability to make connections and find meanings in art that goes beyond the art itself. If you think otherwise, you might have been assigned cop at birth. If someone tells you you’re wrong for finding personal meaning in art, especially meaning that improves your life, I’ll fight them. We’ll do it behind the water tower after school. I asked Coach and he already said it’s ok.

There is a disconnect between Ranma ½ and the reputation of Ranma ½. For decades, just the premise of the series has evoked all kinds of questions in audiences but doesn’t seem particularly interested in providing any answers. For queer readers, like me, the series might end up falling short of the reputation preceding it. However, Ranma ½ also isn’t the first work to play in this space. For as long as there has been a line between genders, people have wondered about crossing that line and coming back again. What authors bring to that space and what they take away is also a reflection of them personally as well as the time they are writing in. Ranma ½ is iconic in space but it is also just one entry in a thought experiment spanning all of recorded history and beyond. So let’s take a moment to look at some works that either precede or follow Ranma and what those authors are trying to express.

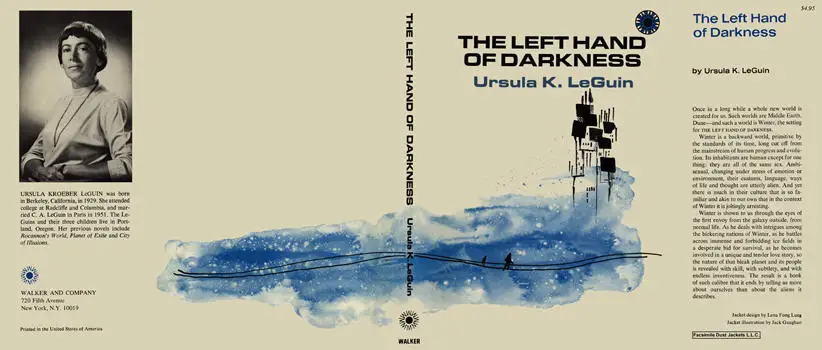

–The Left Hand of Darkness–

Ursula K. Le Guin is a difficult author to talk about. It’s not an exaggeration that without her contributions, modern sci-fi and fantasy wouldn’t exist. Her 1969 novel The Left Hand of Darkness solidified her as a pioneering author and is foundational to the sub-genre of feminist science fiction. Framed as a thought experiment, The Left Hand of Darkness is a distillation of Le Guin’s own thoughts on gender, sexuality and feminism into a narrative exploring the prospect of a post-gender world.

This might seem like a hard pivot going from romcom anime to foundational hard sci-fi but I want to move here for a few reasons. There is the argument that Ranma ½ is conservative even for its time. Le Guin’s work predates Ranma by nearly 20 years and is transparently a thought experiment about the nature of sex and gender in society. It’s also a work that does a great job of illustrating how what different authors are looking for in this space is historically grounded. I also read it for the first time recently and it’s been living rent free in my brain.

The events of the story are predominantly told from the perspective of Genly Ai; a pretty gormless dude who demonstrably does not fuck. Genly has been sent as an envoy to the planet Gethen to invite them to join the federation of planets he hails from. The people of Gethen are similar to Genly in almost all ways save one; they have no fixed sex. 5/6th of the time, the people of Gethen have no primary or secondary sex characteristics. In the remaining 1/6th of the time, they basically go into heat, which Le Guin calls “kemmer” and develop sexual characteristics without knowing whether they will be “male” or “female” for that cycle.

If you’re wondering if this means Le Guin planted the seed that would become omegaverse fiction, it was a group effort, but she almost certainly gave it a big push.

Despite living on Gethen for years, Genly cannot put aside his conceptions of rigid gender and sexuality, making it impossible for him to fully understand the people of the culture he’s embedded himself in. In his eyes and in the German language, everything is gendered. Anyone who shows him any consideration must be a woman. Everyone who asserts themselves is a man. Anyone who can beat him up is a manly man. Even though Genly sees women as inferior to men, being “female” on Gethen is a transient state of being and then that person goes right back to being his equal. In a world where women and misogyny do not exist, it became necessary to invent them.

The first-person narration privileges he/him as the natural state of being, which makes Le Guin’s rare deployment of she/her leap off the page. To Genly, unmoisturized as his elbows are, women are more alien and far more frightening than anything else on this world. Worse, anyone could become a woman at any moment; even your homie! In the few cases where Genly does encounter someone he identifies as a woman, he has a strong emotional response that he can never rationally justify to himself. In fact, his narration expresses that he doesn’t feel a need to even try explaining it. He assumes that everyone else would also panic if they found out their best friend was going to be a woman for the next couple of days.

Of course Genly’s hangups around gender also put off the people he is supposed to be courting. In Gethen, people only develop sexual characteristics when they are trying to have sex. In their eyes, Genly is walking around wearing a shirt with “SLUT” printed in bold font on the front. The guy who cannot explain what a woman is when asked spends a large portion of the novel walking around with everyone calling him a pervert. The guy simply cannot stop from pushing himself down flights of stairs when it comes to social faux pas.

Dats me yellin'

Dats me yellin'

Le Guin was writing at the tailend of the 1960s during a period where the feminist movement in America had started to make moves again. At that moment, Le Guin decided to write this novel to process her own evolving feelings and sexuality and gender via a society where everyone is both a man and woman. Genly is a vehicle to explore those questions and look for answers. While I would argue that Genly doesn’t quite totally figure it out, the thought experiment didn’t end with the novel. Le Guin continued to think about these ideas throughout her career. Even publicly addressing and re-addressing her past self 10 and 20 years after publication. Her essay “Is Gender Necessary? Redux” is a remarkable piece. It’s worth reading just for the commentary:

1976 Le Guin: ““He” is the generic pronoun, damn it, in English. (I envy the Japanese, who, I am told, do have a he/she pronoun.) But I do not consider this really very important.

Annotation by 1987 Le Guin: [I now consider it very important.] “

–Zenbu Kimi no Sei (All Because of You)--

Asazuki Norito’s Zenbu Kimi no Sei falls into the subgenre of gender transformations wherein a character wakes up one day and finds that their sex has changed. The field of stories stemming from a similar premise is surprisingly crowded. Maybe you’re just defenseless against magic, divine intervention, etc. when you’re asleep. Maybe people used to change sex all the time, but now they don’t because of woke. Zenbu Kimi no Sei stands out in how it explores the ideas of gender, sex and sexuality in the context of a relationship. In some ways, it’s treading some of the same ground as The Left Hand of Darkness albeit approaching from the opposite direction.

The premise of the story is going to sound very familiar to anyone that has read “one of these.” Sagimiya Ryou is smitten with a beautiful older student; Mikami Nagisa. He prays to become someone special to Nagisa and wakes up as a girl (as one does). In this setting, people will sometimes develop a condition where their sex changes “whenever their heart flutters.” Even though the condition is rare, it just so happens that Nagisa also has it, and the two of them become roommates in their high school dorms.

Everyone over 30 reading this just turned to nobody and whispered “they were roommates.” Don’t worry. I’ll keep it a secret between us.

Nagisa is a fascinating take on a character in this sub-genre. Unlike Ryou who develops magical gender reversal symptoms as an adolescent and sees himself as a guy who turns into a girl, Nagisa has had this condition since birth. They don’t even know what their “true” sex actually is and believe their position is unique among the small number of people who share the condition. Nagisa understands themselves as both fully a man and fully a woman and that fluidity is central to how they understand themselves as a person in the world. However, they still live in a world of binary gender expectations, and being themselves has meant living a life out of step with everyone around them.

In flashbacks, we get glimpses of how their situation has developed. As a child, it wasn’t that big of a deal for them to be a boy one day and a girl the next since young kids aren’t gendered all that differently. However, those paths started to diverge as they became an adolescent. With age comes expectations and Nagisa finds themself increasingly alienated in a world that wants them to choose a lane and stay in it. Nagisa has made the decision not to date anyone out of fear they wouldn’t fit into that person’s expectations, but it also seems like they don’t have any close friends or even people that know them well.

In a later scene, Nagisa mentions having a younger brother but jokes about how it’s difficult to tell which of them is actually the “oldest son.” More than just romantic and personal relations, familial relationships and the expectations that stem from them are heavily gendered. Something like being the “oldest son” can carry a lot of weight in some families, and it’s not a role Nagisa can fill without giving up a part of themselves. They try to laugh it off, but I was left with the impression that their gender has been a source of contention at home and is the reason Nagisa elected to live in the dorms away from their family.

In many ways, Nagisa’s character feels like a reversal of Genly “CEO of believing blonde women naturally have black eyelashes” Ai’s position in The Left Hand of Darkness. Genly is a binary man on a planet where those ideas don’t exist. Nagisa is a fluid person living in a world where every action they take and relationship they form is trying to force them to give up part of themselves. Maybe you can get a square peg into a round hole with enough force but it’s going to end up damaging the peg.

Ryou’s situation is appreciably different but inextricably related. He starts the story seeing himself as a fairly normal guy with a crush on a girl. As he and Nagisa start dating though, he finds himself in a relationship where at any point he may be seen as a straight man, straight woman, gay woman or gay man. The world’s first single person game of gender four square. The norms of dating are themselves extremely gendered and in their relationship are constantly shifting. This is a particularly salient pain point early on.

Should they hold hands when they’re both guys? When they’re doing the same as girls, do other people assume they’re just friends? Who is supposed to pay when one of you changes sex during the meal? Did I leave the oven on? What does it mean to be a true top in this situation? These are all questions that the two end up having to contend with but seem to weigh more heavily on Ryou since all of this is new to him.

There’s another later scene that sticks out to me. Ryou and Nagisa are comfortable enough together that Nagisa wants to meet Ryou’s family. It doesn’t register to them that they are presently a guy and Ryou is a girl. While polite at first, Ryou’s mom later admits to him privately that she was worried at first that her oldest son had brought a guy home and might have really become a girl afterall (the horror!). She was relieved to find out that Nagisa has also been bitten by the gender bug and immediately starts referring to Nagisa exclusively as a woman despite only having ever interacted with them as a man. Why? Because it makes her more comfortable to think about her kid being “normal.”

At first, I thought this whole scene was a little corny but a second read to prepare this post made it hit me so much harder. It also happens to be one of the very few times the pair interacts without someone outside of the overwhelming queer supporting cast.

Eventually, the reason behind the sex swapping is literal divine intervention. Channeling the spirit of Shinzo Abe, the gods decided that the best way to address issues with declining birth rates would be to make anyone who prays to find a romantic match start swapping sex giving them double the options! The gods in this series are apparently to sex as Metroid Space Pirates are to tubes.

tuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuubes

So swapping was intended to be in the interest of promoting heteronormative relationships and sex purely for the purpose of conception; an extremely conservative plan. Once someone finds their match and does the deed, their body will stop changing meaning a person can’t move into “adulthood” without fitting themselves into a cishet identity.

This revelation leads to some of the best introspection in the series with the main characters both struggling to imagine a happy life where they’ve rounded off their edges. Thankfully, deus ex machina saves the day when the gods decide to toss out that whole plan and allow anyone to change sex whenever they want to for any reason. Yes, Nagisa and Ryou literally move heaven and earth creating a post-gender society via their love for each other. It might seem like I’m spoiling a lot here but there’s so much between the start and finish I’ve deliberately left out. In particular the author and I seem to agree that the side characters and their issues are even more interesting than the main couple.

–Daily Life In TS School--

I first became aware of Kaneko Naoya’s Daily Life in TS School when a friend brought it up with a suggestion and a warning that it might be a little goofy and kinda trashy. One day, after waking up to find out I had lost some more of my civil rights, I was in the mood to read something a little goofy and kinda trashy. If that’s all this series was though, I wouldn’t be sitting here writing about it. While there are parts of the series' relatively short run that dip into the kind of exploitative fan-service at home in my old volumes of Negima!? my mom keeps mailing me, underneath that was a surprisingly wholesome and earnestly told story about gender exploration and identity. It’s stuck with me ever since and was the reason I first wanted to write this piece.

The story of Daily Life in TS School revolves around a cast of characters and their…daily lives in an all-boys school. It’s really right there on the tin. However, this is another “one of those.” A mysterious condition has started to emerge among adolescent boys where they turn into girls sometimes and this school has been set up to accommodate them. What triggers the transformation varies from person to person. My personal favorite is the character that transforms when they’re irritated. However, they like being a girl so much that they make sure to always be just a little bit angry; the Incredible Hulk of gender.

In essence, almost every character is some shade of Ranma. Some characters are ambivalent, some dive headfirst into femininity, a few feel ashamed or embarrassed by their situation and try to avoid transforming. That element of control in how different characters deal with their own personalized version of the button that turns you into a girl forms the backbone of the series’ comedy and drama.

As a survivor of an all-boys high school, I can verify that the series' comedy nails the vibe. If you found out that your friend turned into a girl whenever they got aroused, you would absolutely try to prank them with it. You’d type 58008 into a calculator and hand it to them upside-down or see just how vague you could make a double entendre while still getting them to transform. There are levels of #gotem in this series the likes of which were previously only thought to be only theoretical. Impressively, it also never crosses over from ribbing into bullying. It's a hard balance to strike but everything works here because the characters also clearly care about each other.

That mutual support only factors heavily into the drama and the shared underpinning of mutual support keeps everything moving smoothly. When the series decides to shift into issues of identity, sex and gender, it hits pretty hard. When the students reach the end of adolescence, they typically lose their ability to transform. Eventually, the series introduces an alumnus who has come back for a student teaching rotation only to realize that losing their ability to transform also meant losing a part of themselves that they never properly appreciated. The focus of the chapter is really on that teacher both mourning and trying to reconnect with this feminine part of who they are. All things considered, it’s really well done and connects the goofy premise of the series with some very real ideas about a loss of flexibility in expression as a person gets older.

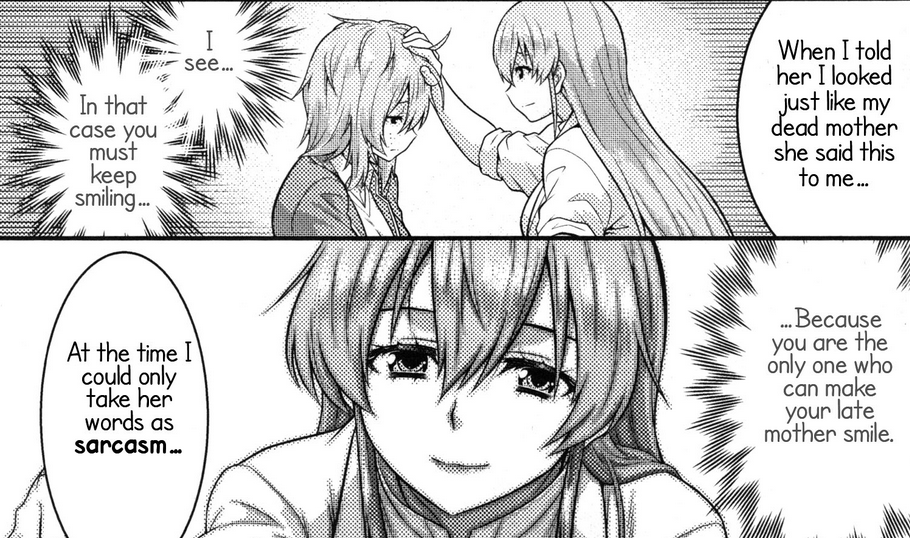

Toward the end of the series, another character unpacks their resentment of their transformation. When they transform, they’re a dead ringer for their recently deceased mother and still haven’t been able to process her passing. They have learned in maybe the hardest way possible the wisdom of the elder gays; “You aren’t going to look like those top 1% OnlyFans models. You’re going to look like your mother.” It’s a genuinely heavy arc that got some feelings out of me.

Daily Life in TS School is a fascinating series that sounds like it shouldn’t work as well as it does. Having written out the last few paragraphs I’m even starting to doubt myself. Messy as it is, it’s stuck with me in the way that only a 6 or 7/10 series can even if I'm not sure I would recommend it. The secret sauce that pulls everything together is the series' genuine effort to take the “what if there was a whole school of Ranmas” premise and explore where that might lead for better and for worse.

That same energy can be found in their other serialization; Vignette Witch! In that series, a boys class gets isekai’d to a pocket dimension. The only way to escape is for the students to magically become girls and train as witches until they accumulate enough magical power to punch through dimensions. I was reading it thinking “Ha! I wouldn’t have a problem with this” and then a very trans character stepped forward and said “Ha! I don’t have a problem with this.” Turns out being trans also makes you a magical prodigy and lets you talk to dragons, which I thought we all agreed not to talk about publicly.

Archmage and Dragonlord just like Erreth-Akbe

As an aside, If you told me that character was plucked out of Le Guin’s Earthsea cycle, I’d 100% believe you. The series was unfortunately canceled early on but they’ve announced they’ll be coming back with another gender bender comic and a new publisher. Honestly, I’m not sure I have it in me to love anything as much as they seem to love making these comics.

-----------------

Wrapping things up, you could write a book about the influence of Rumiko Takahashi’s works on art, comics and animation the world over. Even as someone who hasn’t directly read Ranma or any of her other works, I’ve also still been influenced by her. Even if she as an author and Ranma ½ as a series weren’t as invested in the questions of sex, gender and sexuality posed by the series, having those ideas blasted out via an international smash hit inspired others to play in that space. Some of those people have created their own works and found their own answers.

It’s a time honored tradition pre-dating Le Guin’s “Left Hand of Darkness” and even Greco-Roman myths. As always, the specific flavor of questions asked and answers found depends on historical context. Le Guin’s writing is heavily influenced by her own experiences with sex and gender living in the late 1960’s. That it still feels so contemporary probably isn’t a great sign! Looking at Zenbu Kimo no Sei and Daily Life in TS School as examples of contemporary work, there are some commonalities that might speak to the present moment. Both of these are stories about multiple characters finding and building community. They’re also stories where the character’s personal resolution has a transformative impact on the world around them, even opening doors for others to be more expansive in their own gender expression. As a bonus there is far less emphasis on homo and transphobic humor.

I’m curious what the work of another generation of authors and artists will look like and what kinds of social forces they will be responding to. Surely, some of them will have been influenced by works like "Daily Life in TS School” and “Zenbu Kimi no Sei.” In the moment, the optimism at the heart of these two works is maybe a sign of better things to come.

Until my next entry. Be nice to yourself.