I was assigned doctor at birth (ADAB). Worse, I was assigned a PhD so I’m doomed to always clarify that "I'm not that kind of doctor." Thankfully, my condition was caught early when one of my elementary school teachers, who had been cursed by the god Apollo with the gift of prophecy, took one look at my handwriting and said I had “a doctor’s handwriting.” Also sensing my inability to draw straight lines, my art teachers and parents weren’t subtle in pushing me away from pursuing drawing, even suggesting that it might be something that I would never be good at.

I spent most of my youth and adolescence trying new things and quitting once I'd run out of easy wins, rationalizing that I just lacked talent. Then I became an adult and realized that talent is fake. Big talent just made it up to sell more hobbies. It turns out that what people think is talent is really just the result of effort they haven’t seen #wow #whoa. Emboldened by the idea that I hadn’t been cursed by God, I put pen to paper, both metaphorically and literally, and decided to learn to draw.

The idea was to put together a finished piece once a month. In the interim, I’d watch tutorials, read books and take notes on things I found appealing in the work of other artists. It also helped that I had brain worms for a particular fictional character which is to art skill like nitrous oxide is to cars in The Fast and The Furious series. The bar was set high with an early sketch of Columbo as the Jared Leto Joker but every month I’d still show improvement — sometimes even dramatic improvements. After a year of monthly drawings, I saw all that I had made, and it was decent almost maybe sorta.

Sharing this might be the hardest part of writing this whole thing

Sharing this might be the hardest part of writing this whole thing

Then, I got the idea to challenge myself to draw every day for 90 days and things stopped being fun.

There is a certain magic in being a beginner — you’re just a baby and it’s your first day. Any improvement, any at all, feels dramatic and it’s easy to draw without expectations. Eventually, my progress started to slow despite my expectations for what my progress should be continuing to rise. Like replies missing the joke as a post takes off, plateaus came more frequently and stayed longer. Getting over those plateaus took more time and more effort when at first just thinking about drawing had previously been enough to make big strides. This mounting oppositional force has a name: friction.

As a kid, I learned via rugburns that friction can be painful. As the novelty of being a beginner wore off, it was easier to move on than to push myself. I imagine that I’m not alone in that. Improving at something requires first finding out where your limits are. And bumping into walls, even metaphorical walls, hurts. This time, however, I was committed to running headlong into every wall I could find.

Committing to drawing every day meant stepping out of my comfort zone, drawing things I hadn’t tried before and ending days questioning if talent might be real afterall. Still, I’d come back the next day and try again, often leaving more disappointed than before. Our brains are particularly cruel when it comes to art. They are incredibly good at determining that something is off but awful at identifying why that is. As an added bonus, your eye will always develop faster than your hand so there’s never a point where you aren’t better at seeing your mistakes than you are at fixing them. I have a doctorate in psychology and I’m still always finding new ways our brains are very dumb.

Friction can grind a tool down to uselessness or can sharpen it. How you respond to the discomfort of finding your limits has tremendous bearing on how you’ll mature as an artist. To benefit instead of burning out, you need to allow yourself to feel where, when and how you’re encountering friction. You need to be honest with yourself. You need to be vulnerable. I already knew that friction was a part of the process, but after 90 days of challenging myself I walked away with a different perspective. Friction isn’t just a part of the grander process that is art. Friction is the whole process

But knowing that the friction is the whole thing cognitively doesn’t suddenly make it feel any better emotionally. The discomfort that comes from vulnerability getting in the way of artistic progress is a central theme for one character in Hatsune Miku: Colorful Stage; a game that has no business being as well written as it is. An art teacher gives the game’s obligatory mobage artist character the feedback that “as long as you’re willing to honestly face your art, you can still improve.” On one hand, it’s a reminder that you already have the tools you need to grow. On the other, having a tool and knowing how to use it are two entirely different things.

I edited in the wolf but it's spiritually true

I edited in the wolf but it's spiritually true

Honestly facing your art is both technically and emotionally hard. Your work should just be lines and colors but it is also a reflection of you. No matter how much you try, your art never stops looking like you made it. No one is more aware of their work’s shortcomings than the artist because those same shortcomings already exist in them. I’ve heard it said that what most people think of as style is really just the result of someone getting really good at making the same mistakes. But even if your audience doesn’t know what you were going for, you do. You know that what you made doesn’t measure up to what you had intended. That’s just another point of friction — the tension between your imagination and your ability to actualize it.

Honesty means more than rubbing your own nose in your mistakes. It also means giving yourself credit for the progress you have made even if it isn’t what you were hoping for. I have spent most of my life dwelling on my failings. At first, I thought it gave me the gravitas of a brooding anime protagonist all fourteen year olds aspire to. Underneath that cool anime exterior was an uncomfortable truth: it was a cop out. Being categorically negative was easier than being honest. The sketches I bury in my notebook probably aren't as bad as I think, but calling them failures and flipping to a fresh page is easier than learning from them. That would mean being vulnerable.

What could be more vulnerable than taking that honed observational skill and turning it on oneself. The result is a product of the artist both as observer, producer and product — an expression of themselves mediated through themselves; a self-portrait. As someone ill at ease with both her body and her art, it’s a perfect storm of discomfort for me. As much as I know doing one could be a great source of growth, I just don’t think I have that dog in me. I don’t really know what I have in me sometimes and I’m not sure I want to find out.

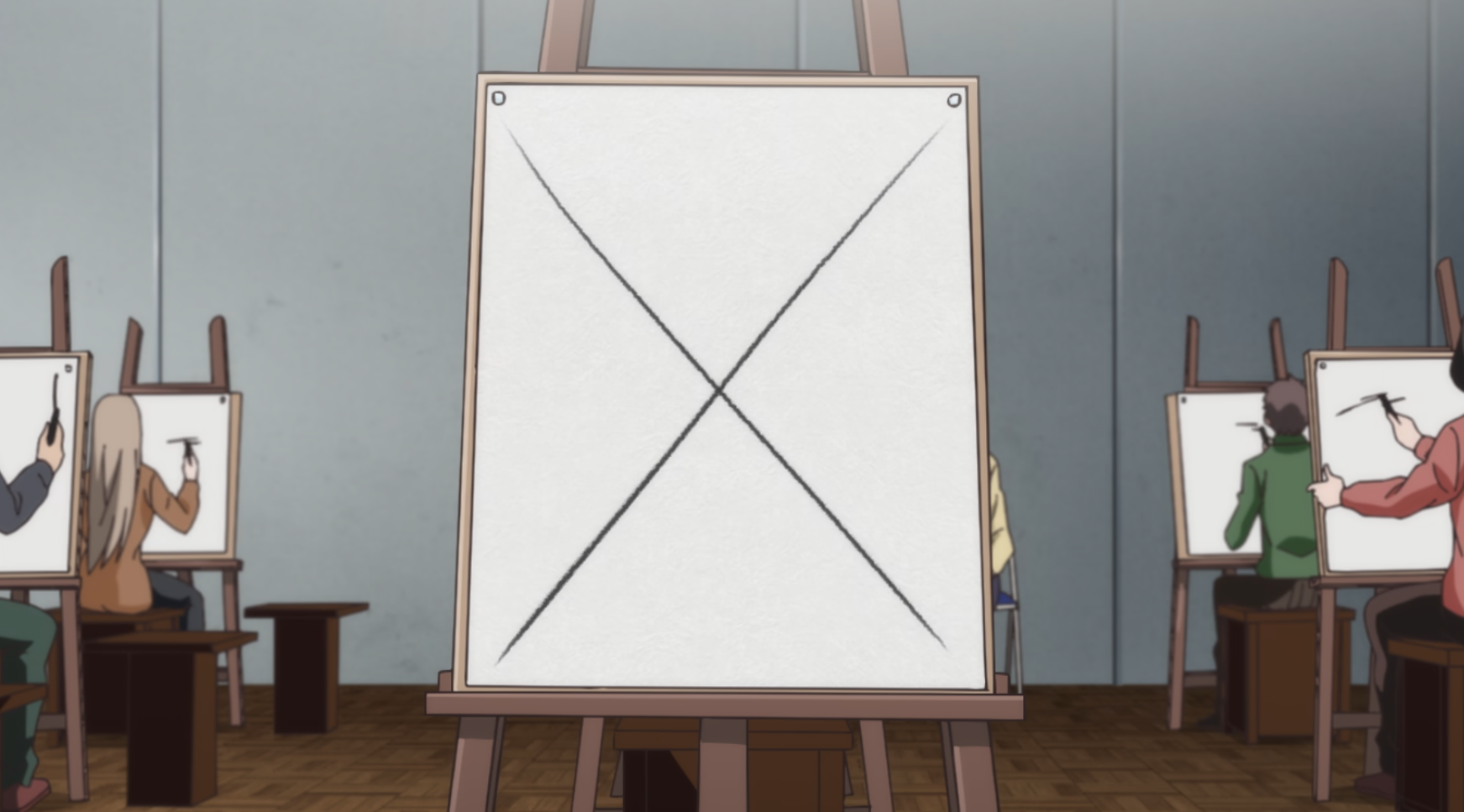

The revealing power of the self-portrait is beautifully presented in the anime and manga series “Blue Period.” The story chiefly revolves around the main character, Yatora Yaguchi, pursuing art professionally. Ryuji "Yuka" Ayukawa is among the revolving cast of characters that cycle in and out of Yatora’s life as he develops both as an artist and a person. Being who I am, it’s hard not to read Ryuji’s highly feminine presentation and shifting first-person pronouns as being somewhere in the transfeminine to non-binary side of the genderfuck spectrum. In the climax of an early arc, Ryuji is asked to draw a self-portrait as part of an art school entrance exam. Instead, they slash an “X” on the canvas in a move that contemporary readers might call “crashing out.”

As the story arc resolves, Yatora and Ryuji are positioned on opposite sides of a privacy screen drawing nude self portraits. Yatora is turning his artistic gaze inward for the first time. He finds it both disquieting and illuminating; describing his body as pitiable and likens it to a hairy eraser. Ryuji, struggling with rejection by their family and their own gender identity, initially refuses to do a portrait despite having suggested it as a source of growth. Their physical nudity is juxtaposed with emotional vulnerability as the pair share their respective motivations, anxieties and identities. It's a perfect encapsulation of how the series deftly interweaves the struggle to grow as an artist and as a person as if they're two sides of the same coin — because they are.

But what if there was another way? In truth, I can understand part of the appeal of AI art. The promise of a world without friction; a world where gratification is immediate and discomfort nonexistent is a much easier sell than trying to pitch someone on the joy of running into walls. Don’t believe me, give it a go and let me know how that works out (editor note: don’t do that). In another life, someone pitched me on the fighting game genre with “you’ll lose your first 500 games before you win one and you probably won’t understand what you did right.” To this day, I have no idea how that worked on me but it did. I’ve since learned that I’m in a minority that some esteemed scholars refer to as “sickos.”

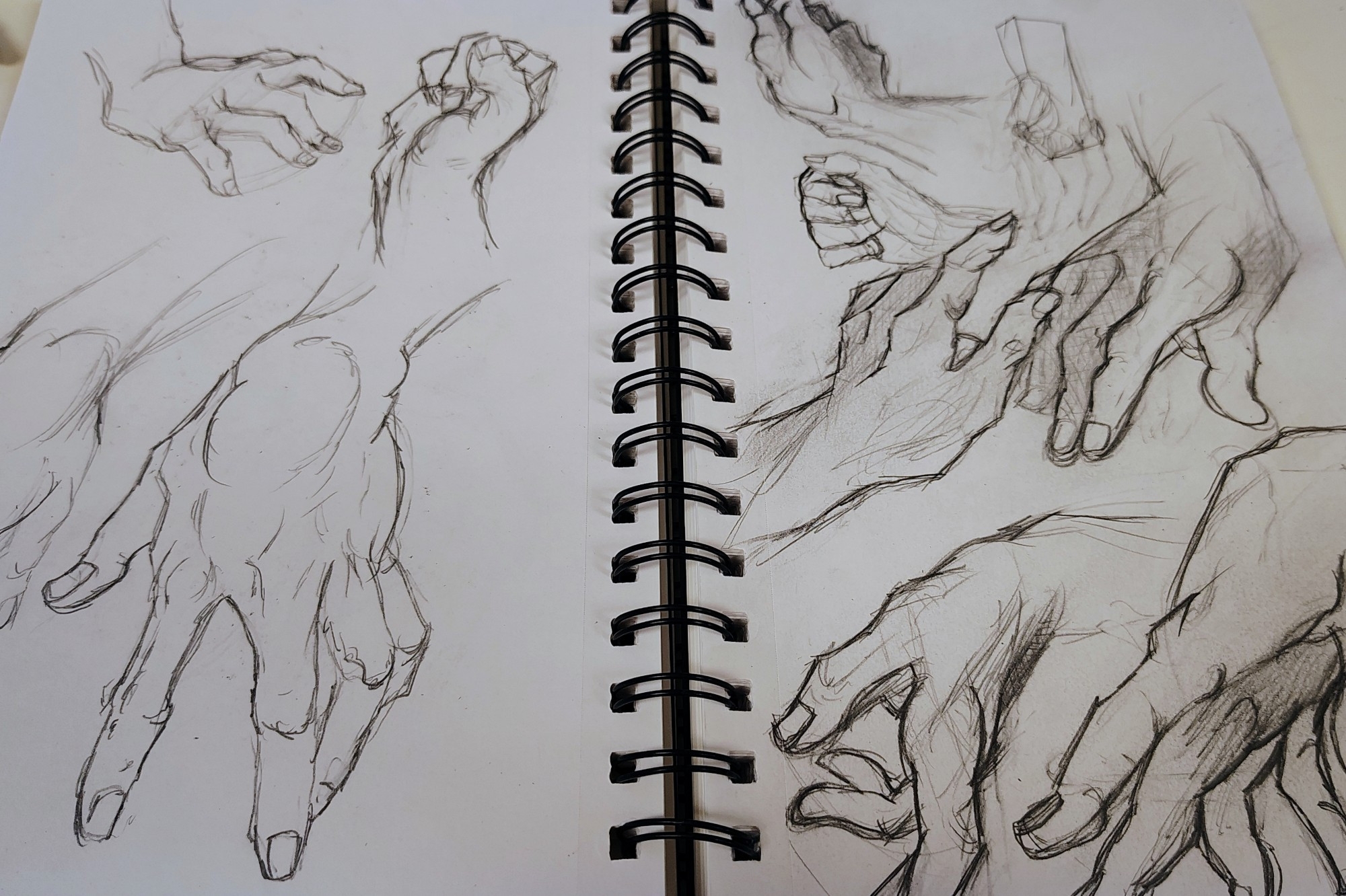

This isn't funny. I only study hands when I'm in extreme distress

This isn't funny. I only study hands when I'm in extreme distress

In the past few years, AI art has ballooned in both popularity and quality. My 90 day art challenge just so happened to parallel an uptick in AI art evangelism. As things really kicked into high gear the image sites I used to find reference quickly became saturated with convincing fabrications that made me yearn for those couple of days people played with DALL-E before we got bored of nightmare renditions of David Lynch’s Dune but with The Muppets. So as I was going through the process of learning to appreciate art as an active process of self-improvement and not a commodity, my socials were full of influencers confidently declaring art is nothing but a commodity. AI advocates aren’t just content to miss the forest for the trees, they’re burning down the forest both metaphorically and literally.

I mercifully thought that no one actually thought that AI will democratize art and oust the gatekeepers of creativity, but had the misfortune of encountering it in the wild recently.Having spent most of my life strictly as an observer of other people’s art, convinced I could never make something anyone would want to see, it’s hard not to have some empathy for the people loudly cheering that AI idea. I’m of the persuasion that most art comes from a desire to communicate something to another person. I remember feeling ashamed of my lack of ability and fearful that an attempt would be embarrassing — that I should be embarrassed. When untold thousands of polished pieces are just a scroll away, it’s easy to slip into thinking of art as only finished products and only valuable if other people value it.

There’s an apocryphal story that says Pablo Picasso was once approached in a cafe. An admirer recognized him and said “Wow, you’re Pablo Picasso” (as one does when they see Pablo Picasso). They asked him to draw them something so he quickly sketched on a napkin. Picasso then asked for a million Francs for the work. The now astonished admirer replied “but you did that in 30 seconds.” Picasso responded “No, it took me forty years and 30 seconds.” No one knows what happened next. I like to think the admirer paid TWO million Frances and everyone clapped.

When you see art as solely as the outcome, as a commodity, every piece is evaluative and every artist only as good as their recent work. The same person I encountered in the wild talking about how artists are gatekeepers also genuinely believe that the majority of human-made art is “bad.” It’s made by amateurs making low-quality works that they should be embarrassed to share. If you earnestly believe that people should mock someone for what they see as mistakes, I can understand why you wouldn’t want to try to make something of your own, nevermind share it. I too wouldn’t want to be bleeding in a pool full of sharks. If only there was another way.

Good news, there is. When you understand that art is a process and not an outcome, things start to look very different. Not too long ago, I had someone comment on a post of mine about that their teachers in art school would stop and ask them where the dogs were if their portfolios were a little too clean during reviews. If a student didn’t have pieces they weren’t happy with, there is a good chance they weren’t challenging themselves enough – i.e. shying away from friction. Not only were mistakes not something to be ashamed of, they were an expectation. I used to feel embarrassed about the number of eraser marks in my sketch books until someone reframed them for me as being part of the history of the piece, proof that I tried and that I kept trying even when it didn’t click the first, second, third or fifth time.

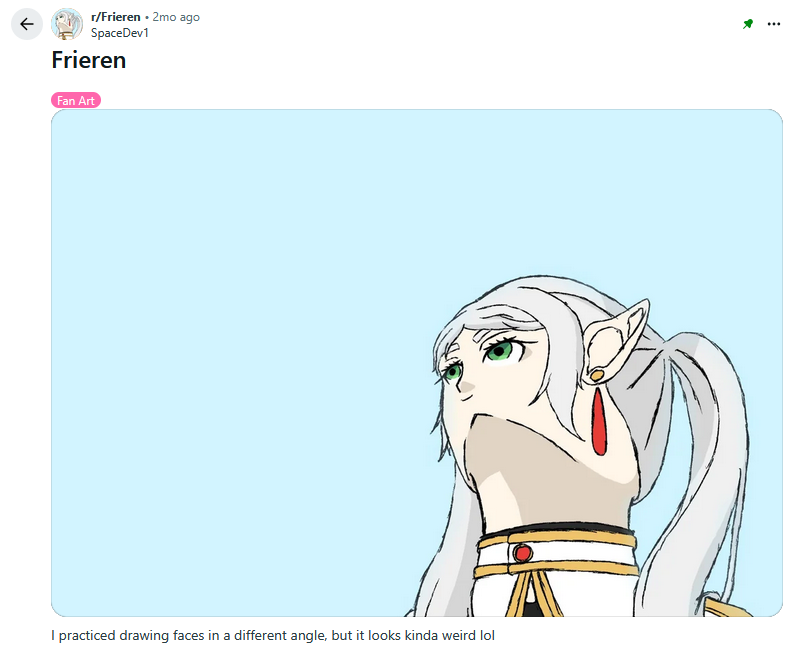

Perhaps you’re familiar with the “Frieren looking up meme.” If you’re not, let me explain. In late 2025, SpaceDev1 posted a fanwork of Frieren from Frieren to the Frieren subreddit. It doesn’t take a fine art degree to see that it’s a little off. Even the artist admits in the post that it came out looking weird. This is the exact situation that stalks the nightmares of someone who thinks people should be ashamed of their mistakes. But the picture immediately exploded in popularity. The voice actress of the character started using the picture as her profile image, professionals, including some who worked on the show, started making tutorials and thousands upon thousands of artists lined up to share their own attempts.

No one was laughing at SpaceDev1; they were laughing together. That specific angle is, in fact, hard as shit to draw. The shared experience of navigating friction can actually be a source of profound human connection. There are no mistakes here; only evidence that someone tried something near the limit of their ability and grew from it. We are only ever truly alone with the discomfort of friction when we’re too afraid to share it. Folks were still tripping over themselves and each other to share their own friction burns, laugh and cheer on everyone else still willing to try. Genuinely, the reaction to this picture is one of the most beautiful things I’ve seen from the internet.

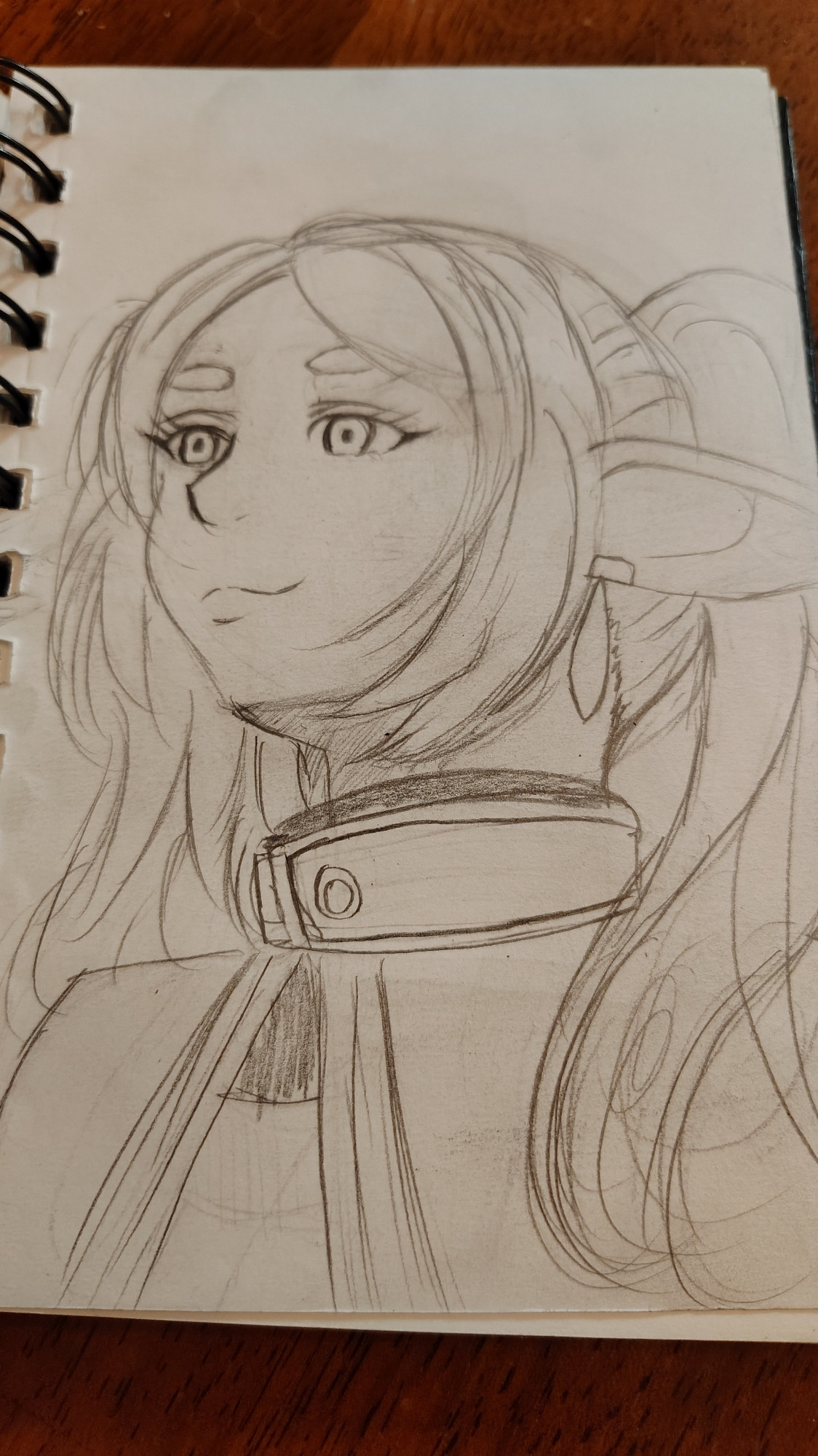

This shit is hard dawg

This shit is hard dawg

In a famous quote, Hayao Miyazaki reacted to a deep learning animation showcase calling it “an insult to life itself.” The line is drawn from a short clip, leading different people to draw different conclusions about the intention behind it. I’m writing this though so I’m basically God until you stop reading. To me, it brings to mind how the experience, joy and frustration that goes into creating art is a profoundly human experience. If we were meant to draw circles easily, our joints wouldn’t be built as they are but at no point in human history has that ever stopped us from trying.

Ironically, or really cynically, OpenAI incorporated a “Studio Ghibli style” image generator into the plagiarism machine (TL note: plagiarism machine means ChatGPT). As much as the guy loudly taking a personal call in the office seemed happy with it, it didn't do anything for me. Sure, the images approximate the color palette and general stylization in a vaguely recognizable way but there’s nothing underneath that surface level similarity. These are refuse destined for a digit landfill once they've poorly done the job of a bitmoji — garbage. Studio Ghibli films (Yes, even Tales From Earthsea) stay with people because of more than just a color palette. The storytelling, visuals and music each speak to something relatably human. You can’t put something like that together without observing and connecting with the world around you.

There is a four second segment in The Wind Rises which took the animator 15 months to complete. It’s jaw-dropping. Everything about it is so deliberate and intentional. It’s easy to imagine all of these characters as having a sense of interiority and life outside of what we see in the frame. It is profoundly human in a way that is only possible to depict when you have put in the work to make connections with other people. More than just the result of fifteen months of effort, It is the result of an entire life and fifteen months. No amount of filters can replicate that.

----------------

Now I’m here at the end of this thing having an entirely new existential crisis having realized that I’ve fulfilled the prophecy of reinventing protestantism from first principles. You start off talking about art and before you know it you’re preaching about the dignity of toil.

Wrapping things up, that initial 90 day experiment was clearly formative for me; so much so that I just kept drawing every day for about six months. I only stopped when the one-two punch of a return-to-office mandate and a long commute made it untenable to find time to draw every day. I still keep a sketching set with me but my tablet has sadly both been collecting dust for the past year. However, even taking out a pencil and paper has become intimidating. Instead of pushing myself, I’ve slipped into the “study vortex.” Like a city planner adding lanes to a highway, I always just need to finish one more study before taking on something more ambitious. But it never seems to fix the underlying issue: shying away from friction.

As much as I can clearly write an exhaustive essay about the virtues of friction, that doesn’t suddenly make it fun to deal with. In the process of writing this, I’ve also come to question whether I’m an artist or just a fan of artists and whether commenting on any of this is stepping out of my lane. Thankfully, working through this essay has helped me to name and confront some of those feelings. Like the kids in the Magic School Bus, who were banished to a hell dimension without friction and forced to play baseball by their sadist teacher, I’m (once again) learning that there can be no moving forward without friction. In fact, friction is just how you know you’re moving forward.

Until my next entry. Be nice to yourself.