You’re Telling Me a Queer Baited This?

Imagine, if you will, a movie theater. The lights come down and I am one of maybe five people waiting for the start of the Hibike! Euphonium movie on an otherwise unremarkable weekday evening. The series up until this point consisted of two seasons following the protagonist Kumiko’s first year as part of the Kitauji High School Concert Band. Having been a band kid in high school (where I was first chair trombone, thank you for asking), it was easy to get invested in the series. The electric romantic chemistry between Kumiko and her friend Reina made it even easier to look forward to whatever would come next. The movie starts with a scene between Kumiko and her childhood friend Shuichi, he confesses to her and Kumiko has a boyfriend before the title even drops. The other four people in the theater could probably hear my hopes deflating like a comically large balloon.

I left the theater so dismayed at my first experience of ‘queerbaiting’ that I put the series behind me. I also wasn’t alone feeling frustrated with a series that had all the signs of a sapphic relationship before swerving with all the force of a stunt driver fresh off the set of Fast 15: The Fury of Atlantis. In fact, if you poke at the ancient scrolls of late aughts online discourse, you will find that it’s the thing the series is primarily known for in some circles. Despite all of that, if you fast forward to the year of Luigi, 2024, I'd confidently tell you Euphonium is not only my favorite series but one filled with rich – albeit deliberately complicated – queer storytelling and deserves both examination and appreciation as such. In many ways, the journey I’ve gone on with the Kitauji Concert Band has paralleled my own personal journey with queerness, identity, confidence and labels.

So yeah, spoiler warning. It’s a good show. Go watch it

So first, what does that term “queerbaiting” actually mean? You don’t need to be Sherlock to realize there are many different definitions floating out there in the Supernatural series of tubes known as the internet, so let’s clarify. In the strict original sense, queerbaiting is a deliberate marketing tactic used to stir audience interest by hinting at potential queer content in a series without any intention to deliver, hence the “bait.”

This particularly became a thing in the ye auld 2010’s when public opinion on same sex marriage was growing increasingly positive and the internet made fandom more accessible than ever before. Before the internet, brave pioneers would have to travel to conventions and speak in euphemisms to find each other like they were trying to get into a prohibition era speakeasy for smut. Fans of Star Trek’s Kirk and Spock in particular adopted the phrase “The Premise” to refer to the pairing and to signal to each other that they were “in the know.”

Personally, I’m in awe of the 1960’s fujoshi snail mailing their handwritten or even typewritten (like with an actual typewriter) nsfw fics to each other. “The Premise” is such a wild rabbit hole that’ll probably be another blog or video someday. But back to the point of departure.

With the rise of Internet fan culture, all it took was some courage and an internet connection. This new openness also meant the fans had greater access to actors, fans and producers than ever before but that would prove to be a two-way mirror.

In a 1979 interview, two-time Columbo killer Wlliam Shatner denied any knowledge of “The Premise”, but by the 2010’s, the cast and crew behind many popular series actively wanted to know fans’ opinions and would seek them out. That included fan fiction and queer readings of the show. If viewership was flagging or a new series needed help establishing an audience, showrunners might add in winks and nods to same-sex relationships as a way to stir the pot. The creators of Rizzoli & Isles have even admitted to doing just that. They would plant suggestions of a relationship between the title characters to court lesbian viewership while mocking those same fans in interviews for picking up on the cues they were putting in there. The 2010’s sure were a time.

However, the term queerbaiting has taken on a life of its own in the years since. Now, it’s not uncommon to see it used interchangeably with “it wasn’t the show I wanted it to be.” The key differences being that the original definition hinges on creator intention. If a creator ends up writing queer themes or subtext without realizing it; such as Gene Rodenberry who was quoted as thoughtful saying “That’s very interesting. I never thought of that before” when made aware of “The Premise,” that’s not bait. If a reader expects a same-sex relationship that doesn’t materialize or go as far as they were hoping, that’s not necessarily bait.

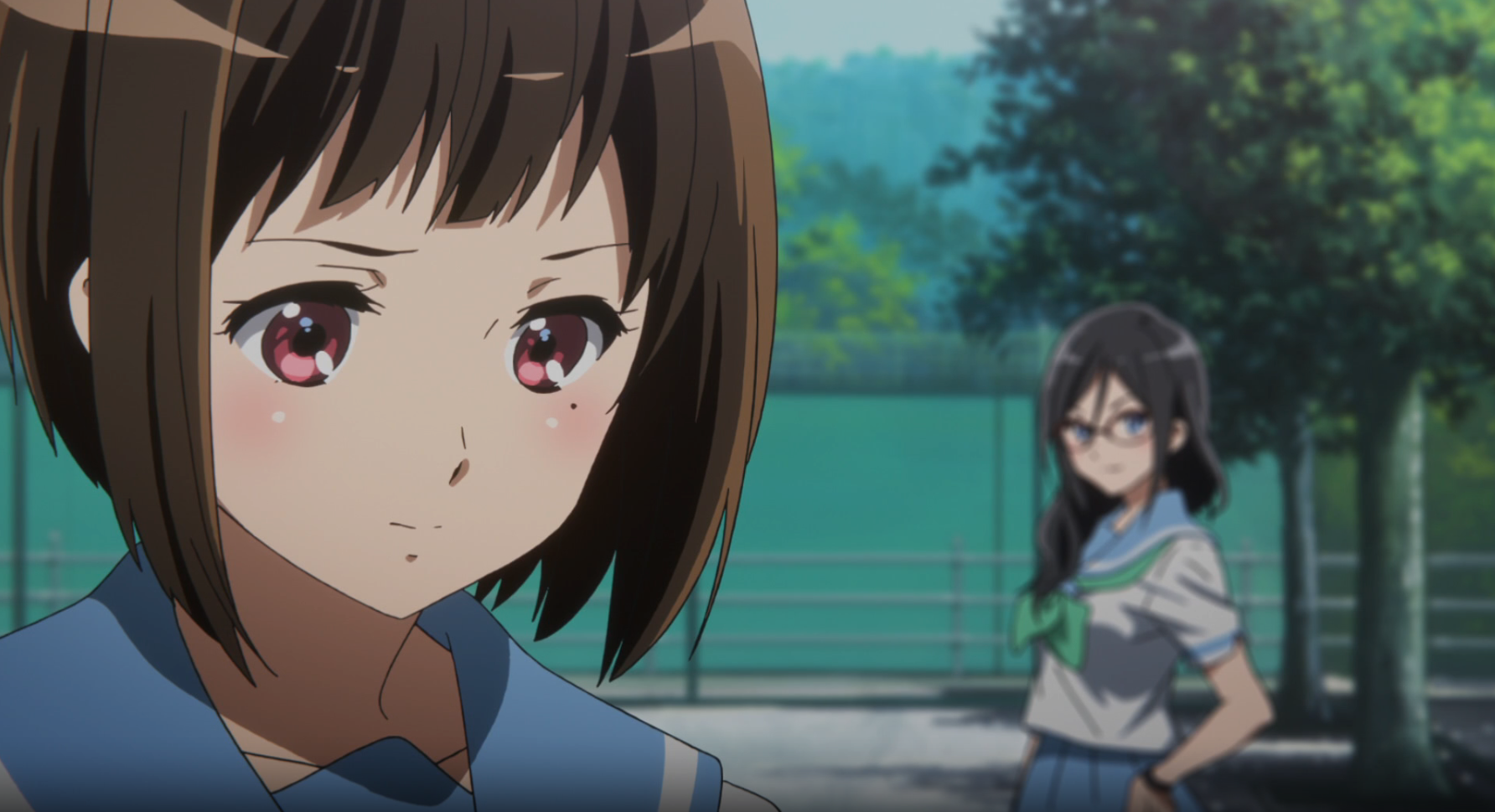

So where does that leave Hibike! Euphonium; a series that has cultivated a reputation as queerbaiting? To answer, it’s best to go to the source; series co-directors Tatsuya Ishihara and Naoko Yamada. In a 2015 interview with Yuichirou Oguro, the two respond to a number of questions about the production of the first season of the show, including the romantic tension between Kumiko and Reina. Of particular interest is the infamous eighth episode of the season where Kumko and Reina climb a mountain together. Along the way, Kumiko likens the sight of Reina in a white sundress to the kind of mythic beauty that would drive sailors to their dive to their deaths at the sight of a mermaid. The episode culminates in Kumiko internally monologuing that she feels like she could die happily as Reina runs her finger over Kumiko’s lips: just extremely heterosexual stuff.

When asked who was responsible for those decisions, Ishihara channels literally physically points at Yamada who goes on to explain that during the storyboarding she came to see the scenes as having the same energy as a “love letter.” She goes on to describe the atmosphere of the episode as “seductive”, even going so far as to describe her mental image of Kumiko as being like “a young boy falling in love one summer.” The interviewer and Ishihara both point out that they felt they were watching yuri (a sub-genre depicting relationships between women) when watching the episode, but Yamada retorts that she doesn’t see it as yuri.

If you’re having a hard time squaring how an episode the director herself described as romantic somehow doesn’t fall under the umbrella reserved for manga and anime depicting romantic relationships between women, you’re not alone. Erica Friedman’s excellent essay collection “By Your Side: The First 100 Years of Yuri Anime and Manga” features a collection of interviews with yuri authors trying to define the sub-genre. In those interview excerpts, the authors, some of whom identify themselves openly as lesbians, draw a line between yuri and lesbian fiction. To them, yuri is primarily for entertainment and not for advocacy or representation – it’s popcorn. Yamada isn’t trying to depict something fluffy and clearcut in her work, she’s aiming to showcase something real, complicated and multifaceted: adolescence.

Personally, this framing speaks to me. There is a reason that Kumiko and Reina’s relationship – and this episode in particular – has loomed over me for almost a decade now. There are many facets to what Kumiko and Reina are to each other, and their dialogue suggests that there is surely some degree of physical and romantic attraction between them. But neither seems to know how to label those feelings and even less how to act on them. It’s complicated. It’s intimate. It’s real.

Yamada’s direction has managed to crystallize a feeling that I imagine is familiar to many queer viewers and all the concert band people I’ve kept in touch with who only realized they were gay years later. It’s that knot in your chest that you never quite untangle until you bolt awake ten years later and realize that night you spent hiking up a mountain with your best friend was a date. It’s a feeling that is rarely depicted in queer media and even more rarely depicted so well.

So if you watched Euphonium and picked up that maybe there was something going on between these two characters caressing each other’s faces and confessing their love, that was a deliberate directorial choice. If you watched Kumiko promise to stay by Reina’s side and Reina promise to kill her if she leaves and thought “that’s just what my straight friends and I do all the time,” I’ll let you figure that out. Apropos of nothing, my favorite 1-2 punch of the specific type of internet commentary you find when researching this kind of stuff is opening with “I’m not gay but…” only to follow-up years later with “So I’ve learned some things about myself…”

However, there is another wrinkle to this story. These elements in the Euphonium anime adaption are not present in the light novel series it is based on. In the novels, Kumiko has an established romantic interest in her childhood friend Shuichi. This leaves the Euphonium anime in an awkward spot as the later seasons try to bring it more into parity with the novel. Kumiko never has the same degree of (or really any) on-screen chemistry with Shuichi. There’s nothing to build their relationship on, so it becomes a nonfactor and the overtures toward it fall flat. The poor guy doesn’t even show up in her big emotional montage reflecting on her high school career at the finale of the series.

The text of the series consequently becomes akin to compulsory heterosexuality (the theory that heterosexuality is taken as normal and enforced on people via social norms). Kumiko never expresses any kind of attraction to her presumed love interest but he’s nice enough and their friends have been pushing them together like two action figures. When he asks her out, she doesn’t have a compelling reason to say no even if she doesn’t seem at all interested in him. Again, this is real. I’ve known of many lesbians who have dated men only to realize later that it’s not normal to not be attracted to your boyfriend/husband.

As much as I could go on to write and others have written about the dynamics between Reina and Kumiko, there is another pair of characters in Hibike! Euphonium that I want to talk about whose queer narrative is both more subtly told and textually concrete; Asuka and Kaori.

In the context of the story, Asuka is the cool upperclassmen character that Kumiko, and everyone else in their school, comes to idolize. She’s beautiful, charismatic and exceptional at everything she puts her mind to: a prodigy. She also only shows the parts of herself she wants others to see and carefully compartmentalizes the rest. In contrast, Kaori is adored by her peers for how genuine and kind she is to the people around her. The two form polar ends of the social dynamic of the band. Since the viewer is seeing the story from over Kumiko’s shoulder, we almost never get to see these two characters interact directly. Rather, we mostly see them mention each other in passing with few exceptions.

That shifts dramatically in the second season. Asuka is revealed to be a child of divorce and living with her overbearing mother who has a strict idea of the future her daughter will have: one that doesn’t include being part of a concert band. When Asuka withdraws from the band, other characters, predictably, hatch a plan to win over Asuka’s mother and allow her to rejoin. What’s less predictable is that the whole enterprise is planned by Kaori. Through this, we get other hints that these two have a closer relationship – like Kaori knowing exactly what sweets to give to Asuka’s mom if you want to get on her good side. What an odd thing for someone to know about the girl who keeps people at a distance!

In a later episode, Asuka invites Kumiko to her house under the flimsy pretense of helping her study. As the two are leaving school, who should they run into but Kaori fully prepared with a bag of the specific buns from the specific bakery that Asuka’s mom likes. Outside of the school, the dynamic between Asuka and Kaori is off puttingly warm. They don’t refer to each other with honorifics, further implying a much closer relationship than we’ve seen. Close enough that Kaori bends down unprompted and ties Asuka’s shoe for her, noting that Asuka only recently bought her sneakers and must not be used to wearing them yet. Again, what an odd thing for someone to know about the girl notorious for only showing people what she wants them to see.

I adore Yamada’s framing in this scene. Every cut is framed specifically to hide each character’s face as a way of building tension, only to be defused as Kaori leaves, creating space for Asuka to turn and ask Kumiko “She’s cute isn’t she?”

Later in the same episode, the two are walking along a riverbank when Kumiko mentions there must be a lot of mosquitoes there in the summer. Asuka mentions that she doesn’t get bit a lot before interjecting that Kaori probably does. She’s so sweet that her blood is probably tasty. Finally, she asks Kumiko if she’s ever looked at Kaori and felt like she just wanted to take a bite out of her. You might think I’m exaggerating to sell a narrative but I’m barely even paraphrasing here.

“You ever look at another woman and just wanna drink her blood” - The most heterosexual woman in the world on Opposite Day or a vampire.

In the novels, there is a side story that’s been gracefully translated by Team Oumae framed as a tear-stained letter written by Kaori to Asuka upon their graduation. In it, Kaori waxes nostalgic about a flirtatious relationship we’ve never been privy to, says she wants to always be together with her, wants to be Asuka’s most important person and asks if she would like to live together. We don’t see Asuka’s response.

We do however see the two of them together when they come to watch the band perform post-graduation. Astute viewers, or people who read the comments of astute viewers on reddit, will notice Asuka and Kaori wearing paired dresses and matching rings. In the third season of the show, Kumiko visits Asuka’s apartment and is surprised to find that Asuka and Kaori are indeed living together. Asuka casually laying her head on Kaori’s lap while she laments how she hoped Kumiko was finally going to come to her for romantic advice with Reina but instead just wanted to talk about band drama. This woman has been waiting for years for Kumiko to come to her for dating advice about another woman only to be reminded that Kumiko might be the most romantically oblivious woman to ever pick up the euphonium.

Bear in mind that two people sharing an apartment together is an uncommon living arrangement in Japan, where it’s more common to live alone or in a dorm-style group house. Kumiko even comments how she’s never even seen two people sharing a room before and Kaori looks at her with an expression I can only read as “Has this bitch really not figured this out yet?”

Like the aforementioned dynamics between Kumiko and Reina, this also isn’t strictly part of the text. There’s nothing in the series to definitely identify Asuka and Kaori as being in a relationship. Unlike the aforementioned dynamic where I can see alternative interpretations, this one takes more effort to see them as anything other than partners than the inverse. I mean, my gosh they were roommates.

In particular, taking this reading of Asuka both explains and enriches her character. We know that she is living under tremendous pressure from her mother who Asuka resents. Her mother slapped her in front of a teacher for refusing to drop out of the concert band. How might she react if she found out her daughter is gay? We also know she has a close relationship with Kaori but we almost never see them together at school. The lack of interaction between them at school makes much more sense if Asuka and Kaori are deliberately trying to be discreet. Kaori tying Asuka’s shoe both shows how close they are and reads as their mutual attempt to clue Kumiko into something. I also don’t think Kaori would start crying while asking Asuka to live with her if she really only wanted to be roommates.

Official art btw

Official art btw

It also adds another level to why Asuka invites Kumiko to her home and actually talks about herself candidly for the first time. She’s seen Kumiko and Reina’s interactions and maybe she’s got a hunch that this new first-year might just be a little bit fruity. Sometimes you can just smell it on someone even if they haven’t realized it yet. Maybe, just maybe, she could be someone that Asuka could share this closeted part of herself with. Her comments about Kaori being cute and wanting to take a bite out of her are probes to see if she’s right and that Kumiko could be that person. Unfortunately, Kumiko somehow remains oblivious, but Asuka is still holding out hope that one day they’ll be able to make that connection.

These relationships in Euphonium are messy, complicated, realistic and definitively queer. As Yamada has said, she didn’t set out to depict easily categorizable relationships but ones that reflect the short and tumultuous time of adolescence: a time of new experiences and self-discovery. There’s so much to chew on with this series but this entry is already getting very long. I haven’t even touched on the companion film Liz and the Blue Bird also directed by Yamada and which prompted a 2022 interview where she was directly asked if she had intended the film as a gay love story.

— — — — — — —

In sitting down to write all this I’ve also come to unpack my own history with this series and how my views on it have evolved. I was a very different person when I sat in that movie theater. At the time, I had just been dumped by my then-fiance, who had decided she’d really rather be with a man, and I'd moved across the country for a job to a city where I didn’t know anyone.

There’s a school of therapy called cinema therapy where people use their connections with media to work through their own issues. I think a lot of people do this intuitively. We invest ourselves in the stories we resonate with and through that connection can receive some catharsis. At a particularly vulnerable part of my life, I had invested a lot in Euphonium as it was one of the first pieces of queer media I had experienced. Only recently revisiting the series at the conclusion of the third season along with my wife forms something like a bookend for me. Now, I’m in a more established place and can look at the series from a perspective without primarily seeking catharsis.

Having had that experience of feeling betrayed, I can appreciate the appeal of series that are canonically queer. There’s a stability in having a creator tell the audience directly that these characters are gay and should be read as such. It makes it safe to get invested in those narratives and no one can take away whatever catharsis you’ve taken from it. It takes energy to be vulnerable enough to allow yourself to be hurt and sometimes you just don’t have any of it to spare.

However, only interacting with series on the basis of what is and isn’t canon limits both the breadth and depth of work you can engage with. These characters and their relationships are queer and are valuable even if none of them look directly into the camera and say “I’m gay.” The complexity stemming from the lack of clean-cut labels is part of what has brought me back to Euphonium for all these years, and I imagine will for many to come. Had I not allowed myself to re-engage with Euphonium after having written the series off, I would have denied myself something beautiful. I also wouldn’t have written fan fiction about Kumiko and Asuka making that long awaited connection or own a bassoon so who can say if it’s good or bad.

Until my next entry. Be nice to yourself.

My Roman Empire